domingo, 24 de febrero de 2013

Phonetics vs. Phonology Part IV

Do you like Rap music? If you like Rap music, you're a lucky! This part I brought two videos where there's rap music, the first one is a girl who is singing rap, explaining what Phonetics is! The other is where two men are singing rap too, explaing with more details.

Phonetics vs Phonology Part III

Here, there are two kind of videos, one is about Phonetics and the other about Phonology.

Phonetics vs. Phonology. Part II

Phonology

Phonology is a branch of linguistics concerned with the systematic organization of sounds in languages. It has traditionally focused largely on study of the systems of phonemes in particular languages, but it may also cover any linguistic analysis either at a level beneath the word (including syllable, onset and rhyme, articulatory gestures, articulatory features, mora, etc.) or at all levels of language where sound is considered to be structured for conveying linguistic meaning. Phonology also includes the study of equivalent organizational systems in sign languages.

The word phonology (as in the phonology of English) can also refer to the phonological system (sound system) of a given language. This is one of the fundamental systems which a language is considered to comprise, like its syntax and its vocabulary.

Phonology is often distinguished from phonetics. While phonetics concerns the physical production, acoustic transmission and perception of the sounds of speech, phonology describes the way sounds function within a given language or across languages to encode meaning. In other words, phonetics belongs to descriptive linguistics, and phonology to theoretical linguistics. Note that this distinction was not always made, particularly before the development of the modern concept of phoneme in the mid 20th century. Some subfields of modern phonology have a crossover with phonetics in descriptive disciplines such as psycholinguistics and speech perception, resulting in specific areas like articulatory phonology or laboratory phonology.

Phonology is a branch of linguistics concerned with the systematic organization of sounds in languages. It has traditionally focused largely on study of the systems of phonemes in particular languages, but it may also cover any linguistic analysis either at a level beneath the word (including syllable, onset and rhyme, articulatory gestures, articulatory features, mora, etc.) or at all levels of language where sound is considered to be structured for conveying linguistic meaning. Phonology also includes the study of equivalent organizational systems in sign languages.

The word phonology (as in the phonology of English) can also refer to the phonological system (sound system) of a given language. This is one of the fundamental systems which a language is considered to comprise, like its syntax and its vocabulary.

Phonology is often distinguished from phonetics. While phonetics concerns the physical production, acoustic transmission and perception of the sounds of speech, phonology describes the way sounds function within a given language or across languages to encode meaning. In other words, phonetics belongs to descriptive linguistics, and phonology to theoretical linguistics. Note that this distinction was not always made, particularly before the development of the modern concept of phoneme in the mid 20th century. Some subfields of modern phonology have a crossover with phonetics in descriptive disciplines such as psycholinguistics and speech perception, resulting in specific areas like articulatory phonology or laboratory phonology.

Phonetics vs. Phonology

Phonetics: (pronounced /fəˈnɛtɪks/, from the Greek: φωνή, phōnē, 'sound, voice') is a branch of linguistics that comprises the study of the sounds of human speech, or—in the case of sign languages—the equivalent aspects of sign. It is concerned with the physical properties of speech sounds or signs (phones): their physiological production, acoustic properties, auditory perception, and neurophysiological status. Phonology, on the other hand, is concerned with the abstract, grammatical characterization of systems of sounds or signs.

The field of phonetics is a multiple layered subject of linguistics that focuses on speech. In the case of oral languages there are three basic areas of study:

• Articulatory phonetics: the study of the production of speech sounds by the articulatory and vocal tract by the speaker

• Acoustic phonetics: the study of the physical transmission of speech sounds from the speaker to the listener

• Auditory phonetics: the study of the reception and perception of speech sounds by the listener

These areas are inter-connected through the common mechanism of sound, such as wavelength (pitch), amplitude, and harmonics.

Phonetic transcription

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is used as the basis for the phonetic transcription of speech. It is based on the Latin alphabet and is able to transcribe most features of speech such as consonants, vowels, and suprasegmental features. Every documented phoneme available within the known languages in the world is assigned its own corresponding symbol.

The difference between phonetics and phonology

Phonology concerns itself with systems of phonemes, abstract cognitive units of speech sound or sign which distinguish the words of a language. Phonetics, on the other hand, concerns itself with the production, transmission, and perception of the physical phenomena which are abstracted in the mind to constitute these speech sounds or signs.

Using an Edison phonograph, Ludimar Hermann investigated the spectral properties of vowels and consonants. It was in these papers that the term formant was first introduced. Hermann also played back vowel recordings made with the Edison phonograph at different speeds in order to test Willis' and Wheatstone's theories of vowel production.

Relation to phonology

In contrast to phonetics, phonology is the study of how sounds and gestures pattern in and across languages, relating such concerns with other levels and aspects of language. Phonetics deals with the articulatory and acoustic properties of speech sounds, how they are produced, and how they are perceived. As part of this investigation, phoneticians may concern themselves with the physical properties of meaningful sound contrasts or the social meaning encoded in the speech signal (socio-phonetics) (e.g. gender, sexuality, ethnicity, etc.). However, a substantial portion of research in phonetics is not concerned with the meaningful elements in the speech signal.

While it is widely agreed that phonology is grounded in phonetics, phonology is a distinct branch of linguistics, concerned with sounds and gestures as abstract units (e.g., distinctive features, phonemes, mora, syllables, etc.) and their conditioned variation (via, e.g., allophonic rules, constraints, or derivational rules). Phonology relates to phonetics via the set of distinctive features, which map the abstract representations of speech units to articulatory gestures, acoustic signals, and/or perceptual representations.

Review

Those pages can help you to improve your knowledge, you can practice in both pages! You'll find games, listening, theories, tests and more! What are you waiting for? Go for them!

http://cambridgeenglishonline.com/Phonetics_Focus/

http://www.cambridge.org/other_files/Flash_apps/Pronunciation/

http://cambridgeenglishonline.com/Phonetics_Focus/

http://www.cambridge.org/other_files/Flash_apps/Pronunciation/

Videos

I brought a couples of videos, the first one is a live video of movements during speech production, it's awesome! I'm sure you'll like it, and the second one is a video related to Speech organs, watch it and don't forget them. Enjoy!

Review, part 3.

Third part of practicing how to describe Consonant Sounds:

Do your best

Good luck

http://emedia.leeward.hawaii.edu/hurley/Ling102web/mod3_speaking/mod3docs/Flash%20Files/combobox_3.swf

Do your best

Good luck

http://emedia.leeward.hawaii.edu/hurley/Ling102web/mod3_speaking/mod3docs/Flash%20Files/combobox_3.swf

Review, part 2

Second part of practicing how to describe Consonant Sounds:

Dear followers practice more how to Describe Consonant Sounds (fricative) :

What is fricative Sounds ?

A speech sound (consonant) in which air is forced to pass through a small opening and creates friction, as in /f/ and /v/

http://emedia.leeward.hawaii.edu/hurley/Ling102web/mod3_speaking/mod3docs/Flash%20Files/combobox_2.swf

Dear followers practice more how to Describe Consonant Sounds (fricative) :

What is fricative Sounds ?

A speech sound (consonant) in which air is forced to pass through a small opening and creates friction, as in /f/ and /v/

http://emedia.leeward.hawaii.edu/hurley/Ling102web/mod3_speaking/mod3docs/Flash%20Files/combobox_2.swf

Review

First part of practicing how to describe Consonant Sounds.

Please dear: learners, practice more and more, this activity teach you how to Describe Consonant Sounds:

Feedback me how you did

Here you go

http://emedia.leeward.hawaii.edu/hurley/Ling102web/mod3_speaking/mod3docs/Flash%20Files/combobox.swf

Please dear: learners, practice more and more, this activity teach you how to Describe Consonant Sounds:

Feedback me how you did

Here you go

http://emedia.leeward.hawaii.edu/hurley/Ling102web/mod3_speaking/mod3docs/Flash%20Files/combobox.swf

Consonant sounds

Summary of English consonants

| [p] | voiceless | bilabial | plosive |

| [b] | voiced | bilabial | plosive |

| [t] | voiceless | alveolar | plosive |

| [d] | voiced | alveolar | plosive |

| [k] | voiceless | velar | plosive |

| [ɡ] | voiced | velar | plosive |

| [tʃ] | voiceless | postalveolar | affricate |

| [dʒ] | voiced | postalveolar | affricate |

| [m] | voiced | bilabial | nasal |

| [n] | voiced | alveolar | nasal |

| [ŋ] | voiced | velar | nasal |

| [f] | voiceless | labiodental | fricative |

| [v] | voiced | labiodental | fricative |

| [θ] | voiceless | dental | fricative |

| [ð] | voiced | dental | fricative |

| [s] | voiceless | alveolar | fricative |

| [z] | voiced | alveolar | fricative |

| [ʃ] | voiceless | postalveolar | fricative |

| [ʒ] | voiced | postalveolar | fricative |

| [ɹ] | voiced | retroflex | approximant |

| [j] | voiced | palatal | approximant |

| [w] | voiced | labial + velar | approximant |

| [l] | voiced | alveolar | lateral approximant |

| [h] | voiceless | glottal | fricative |

Manners of articulation

Stops

Speech segments produced with a complete closure at some point in the vocal tract behind which the air pressure bluids up and can be released explosively./p, b, t, d, k, g/

Fricatives

In the stop [t], the tongue tip touches the alveolar ridge and cuts off the airflow. In [s], the tongue tip approaches the alveolar ridge but doesn't quite touch it. There is still enough of an opening for airflow to continue, but the opening is narrow enough that it causes the escaping air to become turbulent (hence the hissing sound of the [s]). In a fricative consonant, the articulators involved in the constriction approach get close enough to each other to create a turbluent airstream. The fricatives of English are /f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, h/Approximants

In an approximant, the articulators involved in the constriction are further apart still than they are for a fricative. The articulators are still closer to each other than when the vocal tract is in its neutral position, but they are not even close enough to cause the air passing between them to become turbulent. The approximants of English are /w, j, r/Affricates

An affricate is a single sound composed of a stop portion and a fricative portion. In English [tʃ], the airflow is first interuppted by a stop which is very similar to [t] (though made a bit further back). But instead of finishing the articulation quickly and moving directly into the next sound, the tongue pulls away from the stop slowly, so that there is a period of time immediately after the stop where the constriction is narrow enough to cause a turbulent airstream. In [tʃ], the period of turbulent airstream following the stop portion is the same as the fricative [ʃ]. English [dʒ] is an affricate like [tʃ], but voiced.Laterals

Pay attention to what you are doing with your tongue when you say the first consonant of [lif] leaf. Your tongue tip is touching your alveolar ridge (or perhaps your upper teeth), but this doesn't make [l] a stop. Air is still flowing during an [l] because the side of your tongue has dropped down and left an opening. (Some people drop down the right side of their tongue during an [l]; others drop down the left; a few drop down both sides.) Sounds which involve airflow around the side of the tongue are called laterals. Sounds which are not lateral are called central.[l] is the only lateral in English. The other sounds of Englihs, like most of the sounds of the world's languages, are central.

More specifically, [l] is a lateral approximant. The opening left at the side of the tongue is wide enough that the air flowing through does not become turbulent.

Nasals

Speech segments during whose production the velum is lowered closing the entrance to the oral cavity, the air being allowed to escape through the nose. /m, n, ŋ/

Points of articulation

Bilabial

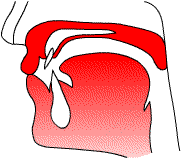

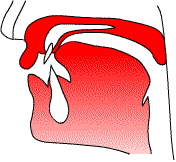

In a bilabial consonant, the lower and upper lips approach

or touch each other. English [p], [b], and [m] are

bilabial stops.

In a bilabial consonant, the lower and upper lips approach

or touch each other. English [p], [b], and [m] are

bilabial stops.

The diagram to the right shows the state of the vocal tract during a typical [p] or [b]. (An [m] would look the same, but with the velum lowered to let out through the nasal passages.)

Labiodental

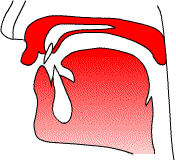

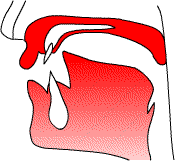

In a labiodental consonant, the lower lip approaches or

touches the upper teeth. English [f] and [v] are bilabial

fricatives.

In a labiodental consonant, the lower lip approaches or

touches the upper teeth. English [f] and [v] are bilabial

fricatives.

The diagram to the right shows the state of the vocal tract during a typical [f] or [v].

Labio-velar

The sound [w] involves two constrictions of the vocal tract made simultaneously. One of them is lip rounding, which you can think of as a bilabial approximant.

Dental

In a dental consonant, the tip or blade of the tongue approaches or touches the upper teeth. English [θ] and [ð] are dental fricatives. There are actually a couple of different ways of forming these sounds:

- The tongue tip can approach the back of the upper teeth, but not press against them so hard that the airflow is completely blocked.

- The blade of the tongue can touch the bottom of the upper teeth, with the tongue tip protruding between the teeth -- still leaving enough space for a turbulent airstream to escape. This kind of [θ] and [ð] is often called interdental.

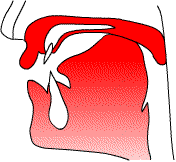

Alveolar

In an alveolar consonant, the tongue tip (or less often

the tongue blade) approaches or touches the alveolar ridge,

the ridge immediately behind the upper teeth. The English

stops [t], [d], and [n] are formed by completely blocking

the airflow at this place of articulation. The fricatives

[s] and [z] are also at this place of articulation, as is the

lateral approximant [l].

In an alveolar consonant, the tongue tip (or less often

the tongue blade) approaches or touches the alveolar ridge,

the ridge immediately behind the upper teeth. The English

stops [t], [d], and [n] are formed by completely blocking

the airflow at this place of articulation. The fricatives

[s] and [z] are also at this place of articulation, as is the

lateral approximant [l].

The diagram to the right shows the state of the vocal tract during plosive [t] or [d].

Plato-alveolar or Alveo-palatal

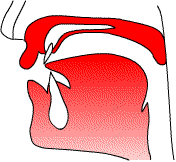

In a postalveolar consonant, the constriction is made

immediately behind the alveolar ridge. The constriction

can be made with either the tip or the blade of the tongue.

The English fricatives

[ʃ] and

[ʒ] are

made at this POA, as are the corresponding affricates

[tʃ] and

[dʒ].

In a postalveolar consonant, the constriction is made

immediately behind the alveolar ridge. The constriction

can be made with either the tip or the blade of the tongue.

The English fricatives

[ʃ] and

[ʒ] are

made at this POA, as are the corresponding affricates

[tʃ] and

[dʒ].

The diagram to the right shows the state of the vocal tract during the first half (the stop half) of an affricate [tʃ] or [dʒ].

Retroflex

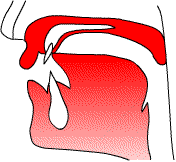

In a retroflex consonant, the tongue tip is curled backward in the mouth. English

[r] is a retroflex approximant -- the tongue tip is curled up toward the

postalveolar region (the area immediately behind the alveolar ridge).

In a retroflex consonant, the tongue tip is curled backward in the mouth. English

[r] is a retroflex approximant -- the tongue tip is curled up toward the

postalveolar region (the area immediately behind the alveolar ridge).

The diagram to the right shows a typical English retroflex [r].

Both the sounds we've called "postalveolar" and the sounds we've called "retroflex" involve the region behind the alveolar ridge. In fact, at least for English, you can think of retroflexes as being a sub-type of postalveolars, specifically, the type of postalveolars that you make by curling your tongue tip backward.

(In fact, the retroflexes and other postalveolars sound so similar that you can usually use either one in English without any noticeable effect on your accent. A substantial minority North American English speakers don't use a retroflex [r], but rather a "bunched" R -- sort of like a tongue-blade [ʒ] with an even wider opening. Similarly, a few people use a curled-up tongue tip rather than their tongue blades in making [ʃ] and [ʒ].)

Palatal

In a palatal consonant, the body of the tongue approaches or touches the hard palate. English [j] is a palatal approximant -- the tongue body approaches the hard palate, but closely enough to create turbulence in the airstream.Velar

In a velar consonant, the body of the tongue approaches or

touches the soft palate, or velum. English [k],

[ɡ], and [ŋ] are stops

made at this POA. The [x] sound made at the end of the

German name Bach or the Scottish word loch

is the voiceless fricative made at the velar POA.

In a velar consonant, the body of the tongue approaches or

touches the soft palate, or velum. English [k],

[ɡ], and [ŋ] are stops

made at this POA. The [x] sound made at the end of the

German name Bach or the Scottish word loch

is the voiceless fricative made at the velar POA.

The diagram to the right shows a typical [k] or [ɡ] -- though where exactly on the velum the tongue body hits will vary a lot depending on the surrounding vowels.

As we have seen, one of the two constrictions that form a [w] is a bilabial approximant. The other is a velar approximant: the tongue body approaches the soft palate, but does not get even as close as it does in an [x].

Glottal

The glottis is the opening between the vocal folds. In an [h], this opening is narrow enough to create some turbulence in the airstream flowing past the vocal folds. For this reason, [h] is often classified as a glottal fricative.Voicing

| voiceless | voiced |

| [p] | [b] |

| [t] | [d] |

| [k] | [ɡ] |

| [f] | [v] |

| [θ] | [ð] |

| [s] | [z] |

| [ʃ] | [ʒ] |

| [tʃ] | [dʒ] |

The other sounds of English do not come in voiced/voiceless pairs. [h] is voicess, and has no voiced counterpart. The other English consonants are all voiced: [ɹ], [l], [w], [j], [m], [n], and [ŋ]. This does not mean that it is physically impossible to say a sound that is exactly like, for example, an [n] except without vocal fold vibration. It is simply that English has chosen not to use such sounds in its set of distinctive sounds. (It is possible even in English for one of these sounds to become voiceless under the influence of its neighbours, but this will never change the meaning of the word.)

Describing consonants

What makes one consonant different from another?

Producing a consonant involves making the vocal tract narrower at some location than it usually is. We call this narrowing a constriction. Which consonant you're pronouncing depends on where in the vocal tract the constriction is and how narrow it is. It also depends on a few other things, such as whether the vocal folds are vibrating and whether air is flowing through the nose.We classify consonants along three major dimensions:

- place of articulation

- manner of articulation

- voicing

For example, for the sound [d]:

- Place of articulation = alveolar. (The narrowing of the vocal tract involves the tongue tip and the alveolar ridge.)

- Manner of articulation = oral stop. (The narrowing is complete -- the tongue is completely blocking off airflow through the mouth. There is also no airflow through the nose.)

- Voicing = voiced. (The vocal folds are vibrating.)

THE PALATE

11. Palate

The palate (pron.: /ˈpælɨt/) is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity. A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but, in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly separate. The palate is divided into two parts, the anterior bony hard palate, and the posterior fleshy soft palate or velum. The maxillary nerve branch of the trigeminal nerve (V) supplies sensory innervation to the palate.

The hard palate forms before birth. If the fusion is incomplete, it is called a cleft palate. As the roof of the mouth was once considered the seat of the sense of taste, palate can also refer to this sense itself, as in the phrase "a discriminating palate". By further extension, the flavor of a food (particularly beer or wine) may be called its palate, as when a wine is said to have an oaky palate.

Function

When functioning in conjunction with other parts of the mouth the palate produces certain sounds, particularly velar, palatal, palatalized, postalveolar, alveolo-palatal, and uvular consonants.

Hard palate

The hard palate is a thin horizontal bony plate of the skull, located in the roof of the mouth. It spans the arch formed by the upper teeth.

It is formed by the palatine process of the maxilla and horizontal plate of palatine bone.

It forms a partition between the nasal passages and the mouth. Also on the anterior portion of the roof of the hard palate is the Rugae which are the irregular ridges in the mucous membrane that help facilitate the movement of food backwards towards the pharynx. This partition is continued deeper into the mouth by a fleshy extension called the soft palate.

Function

The hard palate is important for feeding and speech. Mammals with a defective hard palate may die shortly after birth due to inability to suckle (see Cleft below). It is also involved in mastication in many species. The interaction between the tongue and the hard palate is essential in the formation of certain speech sounds, notably /t/, /d/, /j/, and /ɟ/.

Soft palate

The soft palate (also known as velum or muscular palate) is, in mammals, the soft tissue constituting the back of the roof of the mouth. The soft palate is distinguished from the hard palate at the front of the mouth in that it does not contain bone.

Function

The soft palate is movable, consisting of muscle fibers sheathed in mucous membrane. It is responsible for closing off the nasal passages during the act of swallowing, and also for closing off the airway. During sneezing, it protects the nasal passage by diverting a portion of the excreted substance to the mouth.

In humans, the uvula hangs from the end of the soft palate. Research shows that the uvula is not actually involved in snoring processes. This has been shown through inconsistent results from uvula removal surgery. Snoring is more closely associated with fat deposition in the pharynx, enlarged tonsils of Waldeyer's ring, or deviated septum problems. Touching the uvula or the end of the soft palate evokes a strong gag reflex in most people.

Speech

A speech sound made with the middle part of the tongue (dorsum) touching the soft palate is known as a velar consonant.

It is possible for the soft palate to retract and elevate during speech to separate the oral cavity (mouth) from the nasal cavity in order to produce the oral speech sounds. If this separation is incomplete, air escapes through the nose, causing speech to be perceived as nasal.

The palate (pron.: /ˈpælɨt/) is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity. A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but, in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly separate. The palate is divided into two parts, the anterior bony hard palate, and the posterior fleshy soft palate or velum. The maxillary nerve branch of the trigeminal nerve (V) supplies sensory innervation to the palate.

The hard palate forms before birth. If the fusion is incomplete, it is called a cleft palate. As the roof of the mouth was once considered the seat of the sense of taste, palate can also refer to this sense itself, as in the phrase "a discriminating palate". By further extension, the flavor of a food (particularly beer or wine) may be called its palate, as when a wine is said to have an oaky palate.

Function

When functioning in conjunction with other parts of the mouth the palate produces certain sounds, particularly velar, palatal, palatalized, postalveolar, alveolo-palatal, and uvular consonants.

Hard palate

The hard palate is a thin horizontal bony plate of the skull, located in the roof of the mouth. It spans the arch formed by the upper teeth.

It is formed by the palatine process of the maxilla and horizontal plate of palatine bone.

It forms a partition between the nasal passages and the mouth. Also on the anterior portion of the roof of the hard palate is the Rugae which are the irregular ridges in the mucous membrane that help facilitate the movement of food backwards towards the pharynx. This partition is continued deeper into the mouth by a fleshy extension called the soft palate.

Function

The hard palate is important for feeding and speech. Mammals with a defective hard palate may die shortly after birth due to inability to suckle (see Cleft below). It is also involved in mastication in many species. The interaction between the tongue and the hard palate is essential in the formation of certain speech sounds, notably /t/, /d/, /j/, and /ɟ/.

Soft palate

The soft palate (also known as velum or muscular palate) is, in mammals, the soft tissue constituting the back of the roof of the mouth. The soft palate is distinguished from the hard palate at the front of the mouth in that it does not contain bone.

Function

The soft palate is movable, consisting of muscle fibers sheathed in mucous membrane. It is responsible for closing off the nasal passages during the act of swallowing, and also for closing off the airway. During sneezing, it protects the nasal passage by diverting a portion of the excreted substance to the mouth.

In humans, the uvula hangs from the end of the soft palate. Research shows that the uvula is not actually involved in snoring processes. This has been shown through inconsistent results from uvula removal surgery. Snoring is more closely associated with fat deposition in the pharynx, enlarged tonsils of Waldeyer's ring, or deviated septum problems. Touching the uvula or the end of the soft palate evokes a strong gag reflex in most people.

Speech

A speech sound made with the middle part of the tongue (dorsum) touching the soft palate is known as a velar consonant.

It is possible for the soft palate to retract and elevate during speech to separate the oral cavity (mouth) from the nasal cavity in order to produce the oral speech sounds. If this separation is incomplete, air escapes through the nose, causing speech to be perceived as nasal.

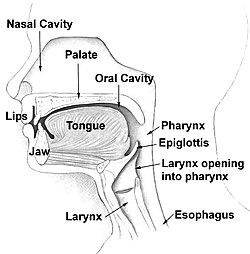

ARTICULATORS

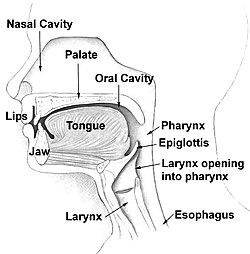

7. The Articulators

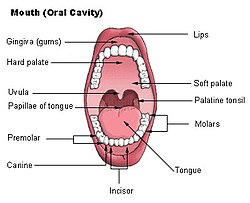

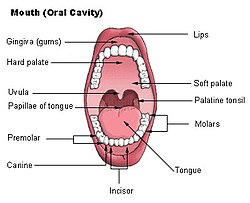

Articulators transform the sound into intelligible speech. They can be either active or passive. They include the pharynx, the teeth, the alveolar ridge behind them, the hard palate, the softer velum behind it, the lips, the tongue, and the nose and its cavity. Traditionally the articulators are studied with the help of a sliced human head figure like the following:The Roof of the Mouth: The roof of the mouth is considered as a major speech organ. It is divided into three parts:

a. The Alveolar Ridge/Teeth Ridge: The alveolar ridge is situated

immediately after the upper front teeth. The sounds which are produced

touching this convex part are called alveolarsounds. Some alveolar sounds in English include: /t/d/.

b. The Hard Palate: The hard palate is the concave part of the roof of the mouth. It is situated on the middle part of the roof.

c. The Velum or Soft Palate: The lower part of the roof of the mouth is called soft palate. It could be lowered or raised. When it is lowered, the air stream from the lungs has access to the nasal cavity. When it is raised the passage to the nasal cavity is blocked. The sounds which are produced touching this area with the back of the tongue are called velarsounds. For example: /k/g/.

8.The Lips: The lips also play an important role in the matter of articulation. They can be pressed together or brought into contact with the teeth. The consonant sounds which are articulated by touching two lips each other are called bilabial sounds. For example, /p/ and /b/ are bilabial sounds in English. Whereas, the sounds which are produced with lip to teeth contact are called labiodental sounds. In English there are two labiodental sounds: /f/ and /v/.

Another important thing about the lips is that they can take different shapes and positions. Therefore, lip-rounding is considered as a major criterion for describing vowel sounds. The lips may have the following positions:

a. Rounded: When we pronounce a vowel, our lips can be rounded, a

position where the corners of the lips are brought towards each other

and the lips are pushed forwards. And the resulting vowel from this

position is a rounded one. For example, /ə ʊ/.

b. Spread: The lips can be spread. In this position the lips are moved away from each other (i.e. when we smile). The vowel that we articulate from this position is an unrounded one. For example, in English /i: /is a long vowel with slightly spread lips.

c. Neutral: Again, the lips can be neutral, a position where the lips are not noticeably rounded or spread. And the articulated vowel from this position is referred to as unrounded vowel. For example, in English /ɑ: / is a long vowel with neutral lips.

9. The Teeth: The teeth are also very much helpful in producing various speech sounds. The sounds which are made with the tongue touching the teeth are called dental sounds. Some examples of dental sounds in English include: /θ/ð/.

10. The Tongue: The tongue is divided into four parts:

a. The tip: It is the extreme end of the tongue.

b. The blade: It lies opposite to the alveolar ridge.

c. The front: It lies opposite to the hard palate.

d. The back: It lies opposite to the soft palate or velum.

The tongue is responsible for the production of many speech sounds,

since it can move very fast to different places and is also capable of

assuming different shapes. The shape and the position of the tongue are

especially crucial for the production of vowel sounds. Thus when

we describe the vowel sounds in the context of the function of the

tongue, we generally consider the following criteria:

• Tongue Height: It is concerned with the vertical distance between the

upper surface of the tongue and the hard palate. From this perspective

the vowels can be described as close and open. For

instance, because of the different distance between the surface of the

tongue and the roof of the mouth, the vowel /i: /has to be described as a

relatively close vowel, whereas /æ / has to be described as a relatively open vowel.

• Tongue Frontness / Backness: It is concerned with the part of tongue

between the front and the back, which is raised high. From this point of

view the vowel sounds can be classified as front vowels and back vowels.

By changing the shape of the tongue we can produce vowels in which a

different part of the tongue is the highest point. That means, a vowel

having the back of the tongue as the highest point is a back vowel,

whereas the one having the front of the tongue as the highest point is

called a front vowel. For example: during the articulation of the vowel /

u: / the back of the tongue is raised high, so it’s a back vowel. On the other hand, during the articulation of the vowel / æ / the front of the tongue is raise high, therefore, it’s a front vowel.

The Jaws: Some phoneticians consider the jaws as

articulators, since we move the lower jaw a lot at the time of speaking.

But it should be noted that the jaws are not articulators in the same

way as the others. The main reason is that they are incapable of making

contact with other articulators by themselves.

The Nose and the Nasal Cavity: The nose and its cavity may also be considered as speech organs. The sounds which are produced with the nose are called nasal sounds. Some nasal sounds in English include: /m/n/ŋ/.

THE RESONATORS

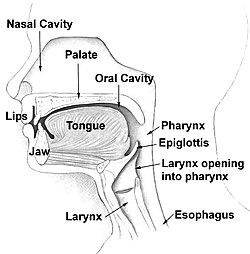

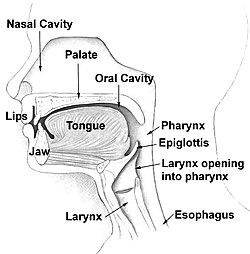

3. The resonators.

They are hollow spaces that change the quality of the sounds. The human speech mechanism has three resonators - the pharynx, which can change its shape slightly; the nasal cavity, which is constant in shape and size, and the oral cavity, which is extremely variable.

4. The pharynx

It's the passage situated at the top of the larynx, communicating with the oral and nasal cavities. Its front wall is formed by the roof of the tongue. The nasal cavity extends from the pharynx to the nostrils, and is separated from the oral cavity by the palate. The entrance to the nasal cavity is the most important resonator, due to the great mobility of its organs and subsequent changes in size and shape. The base of the oral cavity is occupied by the tongue, and the front limited by the lips.

5. Nasal cavity

The nasal cavity (or nasal fossa) is a large air filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face.

Function

The nasal cavity conditions the air to be received by the other areas of the respiratory tract. Owing to the large surface area provided by the nasal conchae, the air passing through the nasal cavity is warmed or cooled to within 1 degree of body temperature. In addition, the air is humidified, and dust and other particulate matter is removed by vibrissae, short, thick hairs, present in the vestibule. The cilia of the respiratory epithelium move the particulate matter towards the pharynx where it passes into the esophagus and is digested in the stomach.

Walls

The lateral wall of the nasal cavity is mainly made up by the maxilla, however there is a deficiency that is compensated by: the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone, the medial pterygoid plate, the labyrinth of the ethmoid and the inferior concha.

The nasal cavity is enclosed by the nasal bone above.

The floor of the nasal cavity, which forms the roof of the mouth, is made up by the bones of the hard palate: the horizontal plate of the palatine bone posteriorly and the palatine process of the maxilla anteriorly. To the front of the nasal cavity is the nose, while the back blends, via the choanae, into the nasopharynx. The paranasal sinuses are connected to the nasal cavity through small orifices called ostia.

They are hollow spaces that change the quality of the sounds. The human speech mechanism has three resonators - the pharynx, which can change its shape slightly; the nasal cavity, which is constant in shape and size, and the oral cavity, which is extremely variable.

4. The pharynx

It's the passage situated at the top of the larynx, communicating with the oral and nasal cavities. Its front wall is formed by the roof of the tongue. The nasal cavity extends from the pharynx to the nostrils, and is separated from the oral cavity by the palate. The entrance to the nasal cavity is the most important resonator, due to the great mobility of its organs and subsequent changes in size and shape. The base of the oral cavity is occupied by the tongue, and the front limited by the lips.

5. Nasal cavity

The nasal cavity (or nasal fossa) is a large air filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face.

Function

The nasal cavity conditions the air to be received by the other areas of the respiratory tract. Owing to the large surface area provided by the nasal conchae, the air passing through the nasal cavity is warmed or cooled to within 1 degree of body temperature. In addition, the air is humidified, and dust and other particulate matter is removed by vibrissae, short, thick hairs, present in the vestibule. The cilia of the respiratory epithelium move the particulate matter towards the pharynx where it passes into the esophagus and is digested in the stomach.

Walls

The lateral wall of the nasal cavity is mainly made up by the maxilla, however there is a deficiency that is compensated by: the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone, the medial pterygoid plate, the labyrinth of the ethmoid and the inferior concha.

The nasal cavity is enclosed by the nasal bone above.

The floor of the nasal cavity, which forms the roof of the mouth, is made up by the bones of the hard palate: the horizontal plate of the palatine bone posteriorly and the palatine process of the maxilla anteriorly. To the front of the nasal cavity is the nose, while the back blends, via the choanae, into the nasopharynx. The paranasal sinuses are connected to the nasal cavity through small orifices called ostia.

6. The Oral

Cavity

- The oral cavity (mouth) consists of two parts: the vestibule and the mouth proper.

- The vestibule is the slit-like spaced between the cheeks and the lips and the teeth and gingivae.

- It is the entrance of the digestive tract and is also used for breathing.

- The vestibule communicates with the exterior through the orifice of the mouth.

- The oral cavity is bounded:

- Externally: by the cheeks and lips.

- Roof of oral cavity: formed by the palate.

- Posteriorly: the oral cavity communicates with the oropharynx.

THE LARYNX

2. The Larynx & the Vocal Folds

The larynx is colloquially known as the voice box. It is a box-like small structure situated in the front of the throat where there is a protuberance. For this reason the larynx is popularly called the Adam’s apple. This casing is formed of cartilages and muscles. It protects as well as houses the trachea (also known as windpipe, oesophagus, esophagus) and the vocal folds (formerly they were called vocal cords). The vocal folds are like a pair of lips placed horizontally from front to back. They are joined in the front but can be separated at the back. The opening between them is called glottis. The glottis is considered to be in open state when the folds are apart, and when the folds are pressed together the glottis is considered to be in close state.The opening of the vocal folds takes different positions:

- Wide Apart: When the folds are wide apart they do not vibrate. The sounds produced in such position are called breathed or voiceless sounds. For example: /p/f/θ/s/.

- Narrow Glottis: If the air is passed through the glottis when it is narrowed then there is an audible friction. Such sounds are also voiceless since the vocal folds do not vibrate. For example, in English /h/ is a voiceless glottal fricative sound.

- Tightly Closed: The vocal folds can be firmly pressed together so that the air cannot pass between them. Such a position produces a glottal stop / ʔ / (also known as glottal catch, glottal plosive).

- Touched or Nearly Touched: The major role of the vocal folds is that of a vibrator in the production of speech. The folds vibrate when these two are touching each other or nearly touching. The pressure of the air coming from the lungs makes them vibrate. This vibration of the folds produces a musical note called voice. And sounds produced in such manner are called voiced sounds. In English all the vowel sounds and the consonants /v/z/m/n/are voiced.

Thus it is clear that the main function of the vocal folds is to convert the air delivered by the lungs into audible sound. The opening and closing process of the vocal folds manipulates the airflow to control the pitch and the tone of speech sounds. As a result, we have different qualities of sounds.

THE LUNGS

1. The Lungs

The airflow is by far the most vital requirement for producing speech sound, since all speech sounds are made with some movement of air. The lungs provide the energy source for the airflow. The lungs are the spongy respiratory organs situated inside the rib cage. They expand and contract as we breathe in and out air. The amount of air accumulated inside our lungs controls the pressure of the airflow.THE ORGANS OF SPEECH

Hello, everyone! I hope you're fine! Before I start explaining the sounds in English, I'd like to introduce the organs of speech, it is necessary.

Besides a brain (and the knowledge of the language), what do you need to use the spoken language?

These are the speech organs.

The speech apparatus is formed by a series of organs and cavities that form a passage from the lungs to the lips and nostrils. The section of this passage that is above the larynx is called the vocal tract.

When we speak, the air we have inhaled into the lungs moves out through the trachea, the larynx and the pharynx, the nose and mouth. The sounds produced in rhis way are called egressive. Sounds produced by taking air into the vocal tract are called ingressive. Sounds in English and Spanish are egressive; certain African languages use ingressive sounds called "clicks".

We will study the speech machanism following the passage of air as we exhale, in the following sequence:

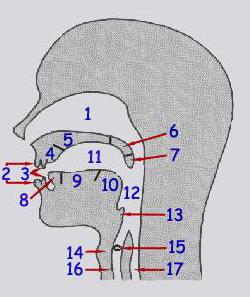

The Organs of Speech

17-esophagus

You can also search more information in the following page: http://www.uiowa.edu/~acadtech/phonetics/anatomy.htm

Besides a brain (and the knowledge of the language), what do you need to use the spoken language?

These are the speech organs.

The speech apparatus is formed by a series of organs and cavities that form a passage from the lungs to the lips and nostrils. The section of this passage that is above the larynx is called the vocal tract.

When we speak, the air we have inhaled into the lungs moves out through the trachea, the larynx and the pharynx, the nose and mouth. The sounds produced in rhis way are called egressive. Sounds produced by taking air into the vocal tract are called ingressive. Sounds in English and Spanish are egressive; certain African languages use ingressive sounds called "clicks".

We will study the speech machanism following the passage of air as we exhale, in the following sequence:

The Organs of Speech

| 1-nasal cavity 2-lips 3-teeth 4-aveolar ridge 5-hard palate 6-velum (soft palate) 7-uvula 8-apex (tip) of tongue 9-blade (front) of tongue 10-dorsum (back) of tongue 11-oral cavity 12-pharynx 13-epiglottis 14-larynx 15-vocal cords 16-trachea | |

|

You can also search more information in the following page: http://www.uiowa.edu/~acadtech/phonetics/anatomy.htm

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)